I. Introduction

"One must ask the mother in the house, the children in the street, and the common man in the market and listen to how they speak, and translate accordingly; then they will understand and notice that we are speaking German to them."

So declared Martin Luther in 1530, defending his revolutionary translation of scripture into the language of everyday life. His insistence on using the vernacular of the marketplace rather than scholarly Latin was radical - promising to remove the barriers between ordinary Germans and divine truth.

Nearly five hundred years later, Sam Altman of OpenAI made a strikingly similar argument about artificial intelligence in his 2023 Congressional testimony: "AI will become a tool that is available to virtually everyone: students, artists, government leaders, voters, and consumers. Everyone should have a voice in how it is developed."

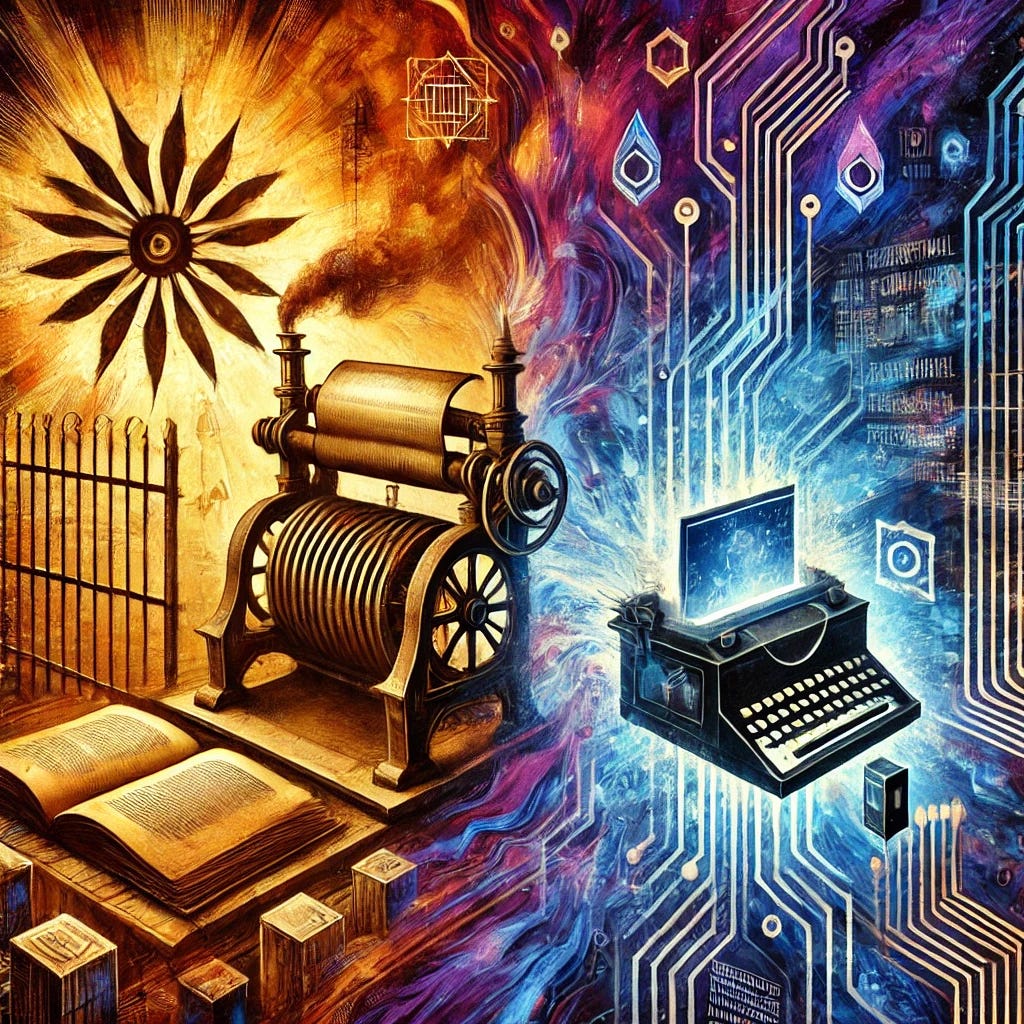

In both cases, a technological revolution promised to bypass traditional gatekeepers and give people direct access to transformative knowledge. Luther believed the printing press and vernacular translation would let ordinary Germans read scripture without priestly mediation. Today's AI evangelists promise that large language models will let anyone access and utilize computational power without technical expertise.

But Luther's campaign for accessibility masked a deeper assumption: he believed that once people could read scripture in their own language, they would naturally arrive at his interpretation - the only correct one. When readers instead reached their own, different conclusions, his response was not celebration but bitter condemnation of their "stubborn misunderstanding." His vision of democratization contained within it a paradox that may illuminate our own moment of technological transformation.

II. The Promise of Democratization

Luther's determination to make scripture accessible wasn't merely about translation. It was part of a broader theological and social vision that challenged the very structure of religious authority. By insisting that ordinary Germans should be able to read and understand scripture for themselves, he was attacking the Catholic Church's position as the necessary mediator of divine truth. No longer would believers need years of Latin education or priestly interpretation to understand God's word - they could encounter it directly in their own language.

This vision was revolutionary in its implications. The Catholic Church had carefully controlled access to and interpretation of scripture for centuries, seeing itself as a necessary guardian and interpreter of divine truth. Latin wasn't just the language of scholarship - it was the language of salvation, carefully maintained by an educated priesthood. Luther's project of translation and printing threatened to bypass this entire structure of religious authority.

Today's AI companies make remarkably similar promises about democratizing access to computational power and knowledge. Just as Luther promised to free ordinary Germans from dependence on Latin-speaking priests, companies like OpenAI and Anthropic promise to free users from dependence on programmers and technical experts. The parallel extends even to the language they use - emphasizing natural, everyday communication over specialized technical knowledge.

But in both cases, this democratization was meant to happen within carefully prescribed bounds. Luther didn't envision a free-for-all of biblical interpretation - he believed the meaning of scripture was clear and unambiguous, requiring only direct access to reveal its (his) truth. Similarly, AI companies promote democratization while carefully shaping how their tools can be used, embedding their own assumptions about "correct" and "responsible" use into the technology itself.

III. Assumptions of "Correct" Understanding

When Luther spoke of making scripture accessible to "the common man in the market," he wasn't merely advocating for linguistic accessibility. "I have not invented an art," he insisted in 1530, "but have only used the language in such a way that Germans can understand what the apostles have said." This remarkable claim reveals the heart of Luther's assumption: he believed he wasn't interpreting scripture at all, but simply making its self-evident truth available to German readers. The Bible, in his view, contained a single, clear meaning that would become apparent to any sincere reader once linguistic barriers were removed.

The irony was that Luther himself had arrived at his interpretation through years of intensive scholarly study, wrestling with scripture in its original languages. Yet he believed that once translated, these hard-won insights would be immediately apparent to any German reader. The complex theological arguments that had led him to challenge Catholic doctrine would somehow become self-evident once scripture was available in the vernacular.

We see strikingly similar rhetoric in how AI companies talk about democratizing their technology. OpenAI's Sam Altman testified to Congress that AI should be "available to virtually everyone" - from students to artists to voters - echoing Luther's confidence in the transformative power of access. Like Luther claiming he had "not invented an art" but simply made the apostles' words understandable, today's AI leaders present themselves not as creating new forms of knowledge or creativity, but as removing barriers to capabilities that should be universally accessible. Like Luther claiming he had "not invented an art" but simply made the apostles' words understandable, today's AI leaders present themselves not as creating new forms of knowledge or creativity, but as removing barriers to capabilities that should be universally accessible.

Yet just as Luther's conviction about biblical clarity ran up against the reality of diverse interpretations, AI companies are discovering that making their technology accessible doesn't guarantee it will be used as they envision. The same tools that can help write business emails or analyze data can be used in ways their creators never intended or actively oppose. The assumption that accessibility automatically leads to "correct" understanding and use is proving as problematic now as it was in Luther's time.

IV. The Reality of Diverse Interpretation

Luther's confident assumptions about the self-evident nature of biblical truth soon collided with a messier reality. Once people could read scripture for themselves, they began interpreting it in ways Luther never intended or anticipated. The Peasants' War of 1524-25 provided perhaps the most dramatic example of this divergence. Rebel leaders, reading the same German Bible that Luther had made accessible, found in it a divine mandate for social revolution. They discovered in scripture not Luther's careful theological arguments about justification by faith, but rather a radical vision of social and economic justice.

Luther's response to these alternative interpretations revealed the limitations of his democratic vision. Rather than engaging with the peasants' reading of scripture, he denounced them as "robbing and raging bandits" and urged German princes to "stab, smite, and slay" the rebels. The man who had insisted on direct access to scripture now found himself arguing that some readings were so dangerous they needed to be violently suppressed. His vision of democratized biblical access had not accounted for the possibility that sincere readers might arrive at radically different understandings of the text.

Today's AI companies face similar challenges as users adapt their tools in unexpected ways. The same large language models intended to democratize access to knowledge and creativity are being used to generate misinformation, create deceptive content, or automate harassment. Their leaders increasingly find themselves, like Luther, speaking from both sides of their mouth - championing democratization while calling for control.

The same Sam Altman who proclaimed AI's democratic potential now acknowledges that "We are aware that AI's impact on society is significant, and we believe that regulatory oversight is crucial to ensure its benefits are widely shared and its risks are mitigated." Similarly, Sundar Pichai, CEO of Alphabet, argues that "We need a balanced approach to regulation that protects society from potential harms while allowing for innovation. It's crucial that governments and companies work together to set boundaries for AI applications." Like Luther calling on princes to suppress interpretations he considered dangerous, tech leaders are increasingly calling for government intervention to control how their supposedly democratizing technology can be used.

The pattern is remarkably consistent across five centuries: when powerful tools become widely accessible, their use often evolves in unexpected directions, prompting calls for control from the very people who initially championed openness. Whether in 16th-century Germany or today's digital landscape, the promise of unrestricted access gives way to the perceived necessity of controlled use.

V. The Control Paradox

The transformation of Luther from champion of accessibility to advocate of suppression wasn't just a matter of changing circumstances - it revealed a fundamental paradox in his vision of democratized knowledge. By 1525, the same man who had insisted on direct access to scripture was raging against alternative interpretations: "If your spirit is the true one, why does it need so much deception, blasphemy, and lies to prove itself? ... Anyone who does not accept my doctrine cannot be saved!" His German Bible was meant to free people from the Catholic Church's interpretive authority, yet here he was, creating new systems of control to ensure "correct" interpretation.

This paradox becomes particularly clear in how Luther responded to those he considered "false teachers." While he had once argued against the Catholic Church's claim to interpretive authority, he now found himself insisting on his own authority to determine correct readings of scripture. The very accessibility he had championed became a source of anxiety - the more people could read the Bible for themselves, the more they might stray from what he saw as its true meaning.

Today's tech leaders find themselves caught in a strikingly similar paradox. Having created tools meant to democratize access to computational power and creative capabilities, they now scramble to control how these tools are used. The same companies that celebrate AI's democratizing potential implement increasingly strict usage policies, content filters, and safety measures. Like Luther, they're discovering that democratization without control can lead to outcomes that threaten their original vision.

This pattern reveals something fundamental about technological democratization: the promise of unrestricted access often contains within it the seeds of new forms of control. Whether in 16th-century Germany or 21st-century Silicon Valley, the democratization of powerful tools tends to produce unexpected results that prompt their creators to implement new forms of oversight and regulation. The question isn't whether there will be control, but what form it will take and who will exercise it.

VI. Lessons for Today

The path from Luther's vernacular Bible to today's AI interfaces might seem long, but the underlying pattern is strikingly consistent. Both movements promised to eliminate privileged intermediaries - whether Latin-speaking priests or code-writing programmers. Both assumed that direct access would naturally lead to "correct" use. And both discovered that democratization brings unexpected and often unsettling results.

Perhaps the most important lesson from this parallel is that claims about democratizing access often mask unstated assumptions about proper use. When Luther said he was simply letting Germans understand "what the apostles have said," he was concealing his own crucial role in interpretation. Similarly, when AI companies present their interfaces as simply making computational power accessible, they obscure how deeply their own assumptions and values are embedded in these systems.

Another crucial insight is that the tension between democratization and control isn't a bug - it's a feature of any attempt to widely distribute powerful tools. Luther's experience suggests that we should be skeptical of any technological democratization that claims to be free from the need for governance or control. The real question isn't whether to have controls, but how to make them transparent and accountable.

VII. Conclusion

As artificial intelligence continues to evolve, Luther's experience with an earlier information revolution offers crucial perspective. The parallel isn't perfect - AI and biblical translation are obviously different in many ways. But the fundamental pattern of promised democratization followed by struggles over control and "correct" use is too similar to ignore.

Luther's journey from champion of accessibility to enforcer of orthodoxy wasn't a simple case of hypocrisy or changed circumstances. Rather, it revealed something fundamental about the nature of democratizing powerful tools: the promise of universal access invariably collides with the messy reality of how people actually use new capabilities. Perhaps instead of being surprised when today's AI companies follow a similar trajectory - from celebrating openness to demanding control - we should recognize this as a predictable pattern that requires thoughtful planning rather than reactive regulation.

This historical parallel suggests that current debates about AI governance might be asking the wrong questions. Instead of arguing about whether to regulate AI, we might better spend our energy thinking about how to build transparent and accountable systems of governance from the start. Rather than pretending that democratized access can exist without control, we should acknowledge that oversight is inevitable and focus on making it serve human flourishing rather than merely corporate or state interests.

In 1530, Luther claimed he had "only used the language in such a way that Germans can understand what the apostles have said." Today's AI companies make similar claims about simply making computational power accessible. Both statements obscure the profound choices and values embedded in these acts of translation. As we continue to navigate our own technological reformation, we would do well to remember that democratization without thoughtful governance isn't liberation - it's abdication.